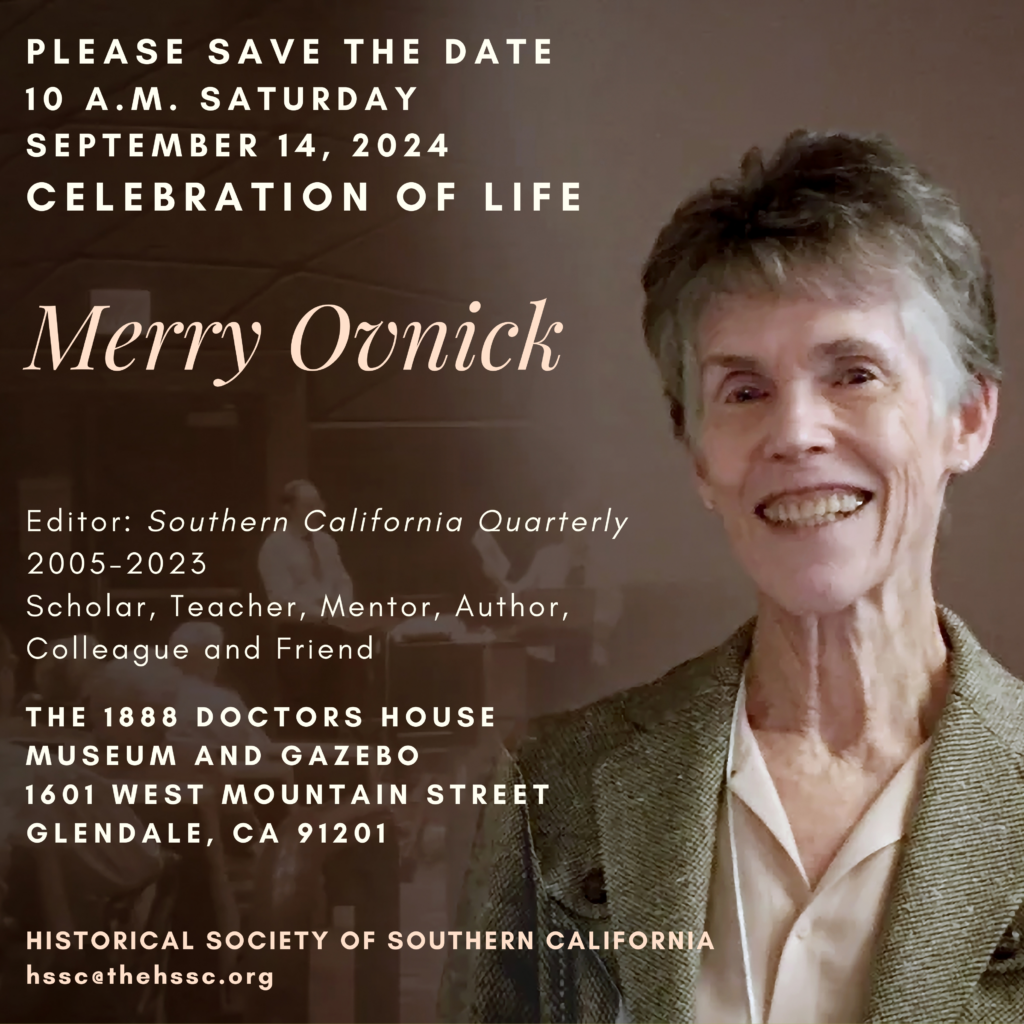

Celebration of Life

10 AM Saturday September 14, 2024

Merry Ovnick

Editor: Southern California Quarterly 2005-2023

Scholar, Teacher, Mentor, Author, Colleague, and Friend

The 1888 Doctors House, Museum and Gazebo

1601 West Mountain Street, Glendale, CA 91201

Please use the form below to sign up to attend Merry Ovnick’s celebration of life:

Cultivating Belonging in Public Spaces

The Historical Society of Southern California

HSSC Programing Calendar 2023-2024

Description of 2023-24 Theme

What does belonging look like in history? When we preserve, research and write history, where do we see ourselves and our communities?

The 2023-24 year’s HSSC program focuses on the theme of belonging in history, and the diverse and innovative ways our communities, educators, historians, and practitioners cultivate belonging in public spaces. This program looks at stories from the past that created spaces of just sustainability in the natural and built landscapes of California. The idea of “belonging” is contested space, and history has proven that laws, policies, and practices have excluded and otherized people in public spaces that were sites of segregation and violence. More importantly, how can we cultivate belonging that honors many stories? California as subject, is the story of success and failure, power and oppression, coalition building and conflict, and environmental conservation and destruction. Join us this year for an impactful and insightful program that features compelling topics to amplify the idea of “belonging,” in the natural and built environments of Southern California.

May 2024: HSSC AUTHOR HIGHLIGHT

Presenter: Donna J. Nicol, Ph.D., California State University Long Beach

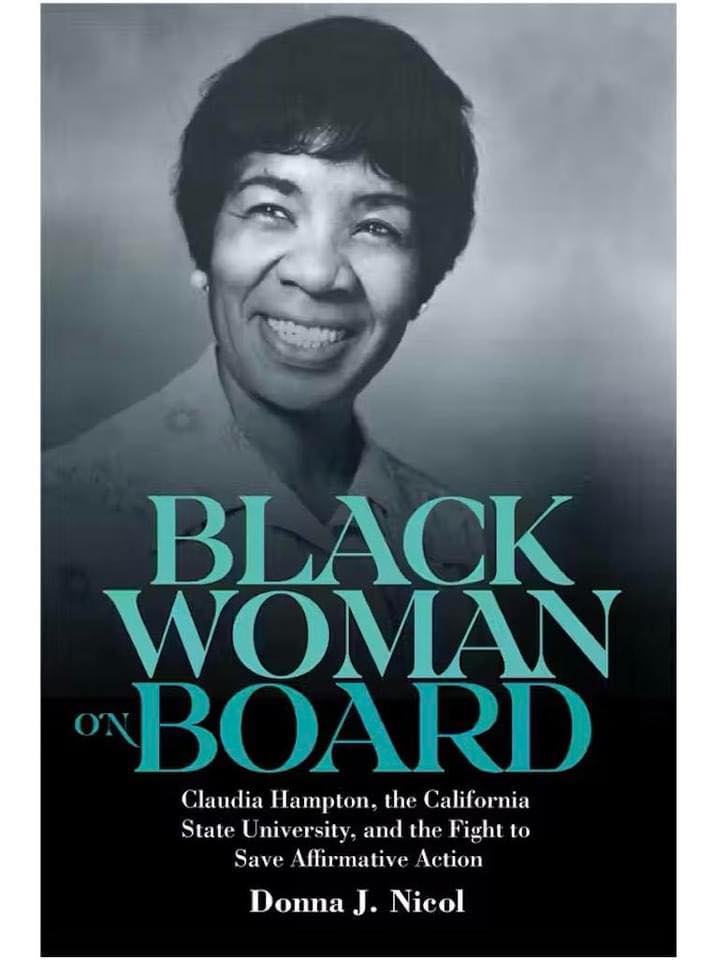

Topic: Book-Black Woman on Board: Claudia Hampton, the California State University, and the Fight to Save Affirmative Action

DATE: Wednesday, May 8th, 2024, 6:00pm-8:00pm via Zoom

Black Woman on Board: Claudia Hampton, the California State University, and the Fight to Save Affirmative Action examines the leadership strategies that Black women educators have employed as influential power brokers in predominantly white colleges and universities in the United States. Author Donna J. Nicol tells the extraordinary story of Dr. Claudia H. Hampton, the California State University (CSU) system’s first Black woman trustee, who later became the board’s first woman chair, and her twenty-year fight (1974–94) to increase access within the CSU for historically marginalized and underrepresented groups. Amid a growing white backlash against changes brought on by the 1960s Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, Nicol argues that Hampton enacted “sly civility” to persuade fellow trustees, CSU system officials, and state lawmakers to enforce federal and state affirmative action mandates. Black Woman on Board explores how Hampton methodically “played the game of boardsmanship,” using the soft power she cultivated amongst her peers to remove barriers that might have impeded the implementation and expansion of affirmative action policies and programs.

Donna J. Nicol is currently the Associate Dean of Personnel and Curriculum in the College of Liberal Arts and a professor of history at CSU Long Beach. Previously she was a professor and chair of Africana Studies at CSU Dominguez Hills and an associate professor of Women’s Studies at CSU Fullerton. Dr. Nicol’s research centers on the role of ‘external agents’ that impact Black student and faculty access and retention in American higher educational institutions, namely civil rights organizations, philanthropic foundations, and university trustee boards. Her work appears in The Feminist Teacher, Palimpsest: A Journal of Women, Gender, and the Black International, History of Philanthropy, Race, Ethnicity and Education, and Al Jazeera English Online.

Dr. Nicol’s new book is available for PreOrder: Black Woman on Board

For book and event information, visit: www.donnajnicol.com

June 2024: HSSC AUTHOR HIGHLIGHT

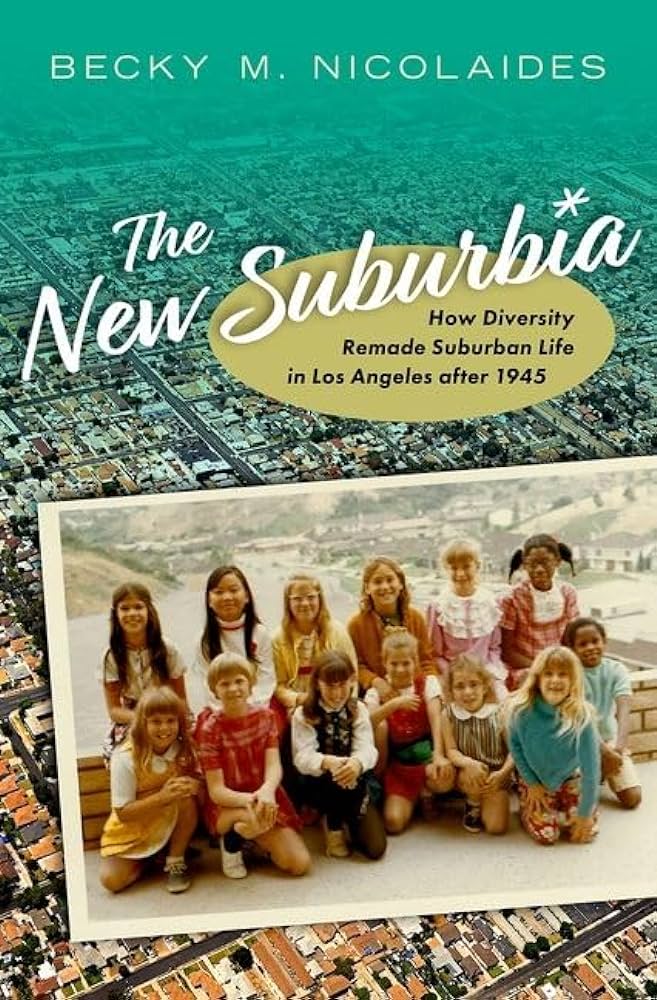

Presenter: Becky Nicolaides, PhD. (Research Affiliate at the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West)

Topic: Book-The New Suburbia: How Diversity Remade Suburban Life In Los Angeles After 1945

DATE: Tuesday, June 4th, 2024, 6:00pm-8:00pm via Zoom

America’s suburbs have been transforming. The conventional story of suburbs as bastions of white, middle-class homeowners no longer describes the suburbs of America’s cities. Today they house a more typical cross-section of the nation–rich, poor, Black American, Latino, Asian, immigrant, the unhoused, the lavishly housed, and everyone in between. Stories of everyday suburban life, in the process, have taken on new inflections.

Nowhere are these changes more vivid than in Los Angeles. In this suburban metropolis and global powerhouse, lily white suburbs have virtually disappeared, and over two-thirds of the County’s suburbs have become majority minority.

Examining this vanguard of change from the postwar to the present, The New Suburbia follows the Asian Americans, Black Americans, and Latinos who moved into white neighborhoods that once barred them. They bought homes, enrolled their children in schools, and began navigating suburban life. They faced a choice: would they remake the suburbs, or would the suburbs remake them? In places like Pasadena, San Marino, South Gate, and Lakewood, suburbanites faced the challenges of living together in difference. Historian Becky Nicolaides explores a range of community experiences, from internal resegregation to suburban poverty, an embrace of law-and-order culture to police brutality, friendly neighbors to social withdrawal. In some communities, diverse residents continued longstanding habits of exclusion and perpetuated metropolitan inequality. In others, they embraced more inclusive, multicultural suburban ideals. Through it all, the common denominators of suburbia remained–low-slung landscapes of single-family homes and families seeking the good life.

An authoritative work based on a half-century of quantitative data and unpublished oral histories and interviews, The New Suburbia explores vital landscapes where the American dream has endured, even as the dreamers have changed.

Becky Nicolaides is an LA-based historian and consultant specializing in the history of suburbs, metro areas, and Los Angeles. She is the author of three books on suburban history, and her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and other outlets.

Becky has consulted extensively for public history projects for Survey LA, LA City, the State of California, and individual communities, and she served on the LA Mayor’s Working Group on Civic Memory. She is currently part of an EU Erasmus+ transnational project focused on the study of suburbanism and urbanism in the EU and US, and is a lead team member of the NEH-supported “LA County Demographic Data Project, 1950-2010.”

She’s taught at UCSD, UCLA, Pitzer College, and Arizona State University West, and is currently a research affiliate at the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. Becky is a co-founder of History Studio, a partnership of award-winning scholars providing expert research, script vetting, and original content for the entertainment industry. She received her BA from USC, and her MA and PhD from Columbia University. Becky is a lifelong Angeleno.

To reach Dr. Becky Nicolaides’ Website for more information click here.

To access the companion page for the book please click here.

For a storymap on LA suburbia, published recently with Jakub Zejdlik, please click here.

To browse Dr. Nicolaides History Studio website, please click here.

To access Dr. Nicolaides Media Kit and information on other published work, please click download below.

November 2023: HSSC AUTHOR HIGHLIGHT

Presenter: Stacy Smith, PhD. (Oregon State University)

Topic: Slavery and Unfree Labor in Early Statehood California.

DATE: Wednesday, November 8th, 2023, 6:00pm-8:00pm via Zoom

Despite its antislavery constitution, California was home to a dizzying array of bound and semi-bound labor systems: African American slavery, American Indian indenture, Latino and Chinese contract labor, and a brutal sex traffic in bound Native American and Chinese women. Using untapped legislative and court records, Stacey L. Smith discusses the rise and decline of these different types of unfree labor in California from the Gold Rush to the Civil War.

Dr. Stacey L. Smith is an Associate Professor of History at Oregon State University where she specializes in the history of the American West during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. She is the author of Freedom’s Frontier: California and the Struggle over Unfree Labor, Emancipation, and Reconstruction (2013).

October 2023

Presenter: Carol Kwang Park

Topic: The contributions, successes, and struggles of Korean Americans in Southern California.

DATE: RESCHEDULED TBA

Korean American History & Identity

This lecture will focus on the untold tales of the Korean American community and how this small population navigated the US landscape in the early 20th century. The Korean American identity has evolved throughout its 120-year history from independence fighters founding the first Korean Aviation School and Corps. in Willows, CA, to a focus on reunification of North and South Korea, and to where we are today. This lecture will draw from the textbook Korean Americans: A Concise History.

September 2023

Presenter: Kristine Ashton Gunnell, Ph.D.

Abstract/Title: Financing Social Change: The Daughters of Charity Foundation and Catholic Efforts to Disrupt Poverty and Empower through Education.

DATE: September 27th, 6-8pm

Since their arrival in Los Angeles during the 1850s, the Daughters of Charity have embraced faith as a tool to advocate for disadvantaged and underserved communities. While their services have changed over the last 160 years, these Catholic sisters continue to cultivate an ethos of care and belonging which crosses race, class, and religious identities as they assist individuals and families navigate the systems which keep people in poverty. Recognizing that transformative social change takes vision, commitment, and funding, the Daughters updated their community’s funding infrastructure by establishing the Daughters of Charity Foundation in 1984. By embracing evolving forms of financing, the Daughters provided their ministries greater opportunities to thrive and promoted the sustainability of their works. This presentation will discuss the Daughters educational initiatives in Los Angeles in the early twenty-first century, and how the sisters’ innovations reflected the long history of women’s efforts to pursue freedom, opportunity, and agency on behalf of the common good in the mythic West.

Bio: Kristine Ashton Gunnell completed her Ph.D. at Claremont Graduate University, where she is currently a Visiting Scholar in its School of Arts and Humanities. She specializes in the history of Women and Gender in the American West, especially the role of religious women in public and private life. Gunnell is the author of Daughters of Charity: Women, Religious Mission, and Hospital Care in Los Angeles, 1856-1927 (DePaul Vincentian Studies Institute, 2013). In 2014, she won the Western Historical Association’s Arrington-Prucha Prize for the best article published on the history of religion in the west and she has published articles in the Southern California Quarterly, Vincentian Heritage, and the U.S. Catholic Historian. Gunnell lives in Simi Valley, California, and she is currently writing a history of the Daughters of Charity Foundation and its strategies to fund the sisters’ social justice efforts in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Presenters:

Rev. Charles Brown-President and Founder of the Compton 125 Historical Society

Pauline Brown-COO, Co-Founder of the Compton 125 Historical Society

Topic: Preserving the History and Legacy of the City of Compton

DATE: September 6th, 6-8pm via Zoom

Join us to discuss the preservation, legacy and the role of the Compton 125 Historical Society for the city of Compton.

1. Historical Landmarks: the importance of preserving iconic landmarks ie. buildings, monuments, and landmarks that hold significance in the city.

2. Cultural Inheritance: discuss how the preservation of cultural traditions, festivals, and customs contributed to maintaining Compton’s unique identity.

3. Historical Exhibits: the role of exhibitions and showcasing artifacts, documents, and artworks that highlight the city of Compton’s past.

4. Community Engagement: ways to involve residents in preserving the city’s history such as through oral history, workshops, and events.

5. Education Initiatives: the importance of educating the younger generation about the city’s history, school programs, tours, and educational resources.

6. Historical Preservation Ordinance: the impact of the legal framework that protects historical sites and structures from demolition or modifications.

7. Public Spaces and Parks: a look at incorporating the element of historical spaces for reflections and appreciation.